Shasta - First North American peak

Mt Shasta as seen from my plane a year and a half before I climbed it

I’m woken by a rustling in the dark and by Matt’s voice outside the tent - “It’s 1am, time to get ready”. I turn over in my cramped sleeping bag, as my brain is struggling to wake up at this unnatural hour. I hear Larry, lying in the middle of the tent, head pointed in the other direction, say “I’m not going. I told Tyler yesterday. I’ve had a good run”. Larry is 66 years old and he started climbing just seven years ago. During that time he has summited five of the “seven peaks”, a list of the highest peaks on each continent, in addition to other mountains. He got the Khumbu cough on Everest shortly before the earthquake in 2015, so he didn’t summit, but still proudly wears the jacket with his Everest sponsors. Caleb, the third climber, is a wiry lightning technician from LA who like me is also a Mazamas member. And Tyler is one of the guides on our climb to Shasta, the volcano we’re attempting to climb today. I breathe a sigh of relief - during my short fitful sleep I dreamt that I slept through the alpine start. It was just a nightmare, probably caused by nerves.

Caleb, the other climber and the third occupant of our tent, is already sitting up, headlamp on, starting to organize his gear for our alpine start up the ridge in an hour. I’m feeling around my sleeping bag to locate my phone, the headlamp and all the other electronics that I’ve stashed away in my bag to protect them from the cold. A few minutes later, I unzip the entrance to our tent and I’m greeted by the moonlit snow slope extending steeply down from the ridge where we’ve erected our tent camp. The night is surprisingly calm. The wind causing my nightmares from the evening has died down. It’s still bone-chillingly cold. I’m thankful for the warm down jacket and for the fact that my boots did not freeze overnight.

As a newcomer to mountaineering, it still amazes me how little time one hour really is. There are so many things to do and prepare, it’s seems like an exercise in military efficiency. In addition to boiling water and making breakfast (a task that on this climb thankfully our guides are in charge of), I need to put my contacts on and get dressed in a very cramped spot with just the light of my headlamp. It reminds me of trying to put a lot of layers on while sitting in a middle seat in economy. I use the opportunity of the relative warmth of the tent to slather on some sunscreen. Then come the boots, the gaiters, downing some hot slush for breakfast and a last bathroom visit by the “pee rock” a healthy distance down the ridge from our camp.

Unfortunately the ridge is quite exposed and the moonlight is reflecting off the snow slopes, making for a well-lit bathroom visit with no privacy. I’m thankful for my “pee funnel”, probably the most useful contraption for girls on a mountain, but I can’t bring myself to crouch for the other type of bathroom visit that I feel I want to make. I’m clutching the “human waste disposal” kit provided by the Forrest Service to climbers on Shasta, which I’ve supplemented with a large compostable bag, but I’m keenly aware that anyone looking from camp can see me there, as can the people on the Avalanche Gulch route, directly under me, whose headlamps are starting to come on as some of them emerge from their tents. I make a mental note to look for a more private spot during our climb.

My guide Matt in the early hours on the Cassaval Ridge, with me following closely behind him

Next, we need to put on harnesses, helmets, gloves, put crampons on, rope up, put on the packs and grab our ice axes and poles. By the time all that is said and done, it’s been well over an hour and end up starting the climb at 2:20am, twenty minutes late. Part of the challenge is that everything that one has to touch is located in separate places - inside the tent, inside the vestibule, outside the tent or in various parts of the campsite. But the bigger challenge seems to be that unless one has a reliable and timed system for getting ready for the alpine start, much like everything on the mountain, all the minor inefficiencies of doing things out of sequence add up to wasted time. And in the alpine, where speed is safety, wasted time can be very dangerous.

The first time Brent and I got ready for a climb in New Zealand, it also took us half an hour longer than expected. We made it up the following day by being extremely efficient and concentrated in our tasks. Brent likes to mentally rehearse the sequence of movements before he goes to bed the night before and I’m doing the same. Still, the lack of sufficient experience can still slow me down if I’m not later focused.

Shasta has always held my imagination ever since I started living in California years ago. It would tantalize me with her double volcanic cone from the window of airplanes anytime I flew up to Portland or Seattle. Like a majestic queen, she would appear on the horizon, towering with her glistening snow-capped sides as I drove along the I-5. And of course, the new age community had created an amazing lore of legends and stories about the mystical aura of the mountain and the higher consciousness beings that are said to inhabit her. Anytime I’ve been in her presence, I’ve felt peaceful and my mind has felt more clear and refreshed - like I’m standing in the presence of a great and benevolent goddess.

I didn’t start seriously thinking about climbing Shasta until Brent and I came back from our nascent mountaineering exploits in New Zealand in the spring. We had set our sights on an expedition in Alaska - climbing the 15,700 ft Mt Fairweather - and I had just under two months to prepare. I had talked to one of the lead guides at AMG (Alaska Mountain Guides) who had encouraged me to get my endurance up by climbing a mountain in the Cascade ranges - Rainier, Mt Hood, Mt St Helens or Shasta. Of these, Shasta and Rainier provided the highest and longest climbs, but Raineer, being so close to Seattle and visible from the city, attracted throngs of would-be mountaineers and all the guided trips for the year were fully booked. Shasta, on the other hands, being more remote and inaccessible, still drew crowds, but nowhere near the level of Rainier.

Brent had found a guiding company that led Shasta not just on the main route of Avalanche Gulch that gets 80% of the climbers, but also along a longer, more technical route over the most aesthetic line on the mountain - the Casaval Ridge. The timing was perfect since Casaval could only be climbed during a narrow window of mid-April to mid-June, where there was sufficient snow on the ridge and SWS had a climb scheduled for early May. At the time, Brent had made other plans, but he was incredibly encouraging and supportive of me going for it.

As soon as I get to the SWS bunkhouse in Shasta, I run into a confident and friendly guy who is sorting through gear. “Hi, I’m Matt, I’m your lead guide for tomorrow”. I immediately feel at ease with Matt - everything from the way he moves to the way he talks and the way he takes me across the street to show me the ridge we’d be climbing conveys a true joy for the mountain and a certain endearing spunkiness. The following day we are joined by Tyler, another guide whois technically based in Montana but in reality lives mostly out of his camper van and Spencer, an anthropology college student who is spending a few months learning how to guide after working as a ski school instructor in Alta.

We start on Bunny Flat with an easy hike up, gaining about 3,000 feet and arrive at the beginning at a nice flat part of the ridge early in the afternoon, where everyone busies themselves with setting up a snow camp. It is my first time camping directly on snow and I eagerly help flatten out spots for the tents. Later in the afternoon the guides go into briefing mode before our climb. We are scheduled to awake at 1am and be roped up and geared up by 2am. Since none of us is a complete beginner, Tyler concentrates on going over the basics of the self-arrest and glissade techniques. Glissading is a type of sliding on the snow that resembles sledding, except without the sled. The key is to control the speed and direction at all times and to never let go of the ice ax. And of course, never to glissade with crampons on. Then the guides go into the roping arrangements. Each guide would take one client on a short rope.

I should pause to say that the statement of one guide short roping each client was a bit of a culture shock for me. I had just come back from New Zealand and my only experience learning mountaineering and climbing peaks had been in an very liberal environment where “clients” are trusted to be grownups and take responsibility for their wellbeing. The subject of short-roping had come up during our training but our Kiwi guides had assured us that this technique was reserved for clients who didn’t have much training or knowledge to navigate without being on a leash. Brent and I were accustomed to leading on a climb and securing each other, as well as having our guide tied in with us on the rope while glacier traveling.

My explanation of what I am used to draws wry smiles from both Matt and Tyler, who says “I will get fired as a guide if I let you lead climb, or if I don’t always have you on a short rope”. Guided climbing in the US, as I come to learn from my subsequent trip in Alaska, comes with 30+ disclaimer contracts and mandatory physician’s certifications characteristic of the most litigious society in the world.

Coming to terms with the inevitability of the short-rope, I resign myself to a short fitful sleep before our alpine start. At some point in the middle of the nightmare caused by the flapping of the wind against the tent, I hear the guides start moving and getting the gas going for melting snow. Then they yell for us to wake up. As Larry abandons the climb, Caleb and I hustle to get dressed and geared up. I barely have time to shovel some warm instant oats in my mouth and we are off.

The outline of the ridge looms ahead of us with snow glistening in the silver light of the full moon. Our small group of five quickly falls into the rhythm of putting one foot in front of the other, zigzagging up the snow. We stop every hour to hydrate and eat. I am thankful for my Aarn pack front pockets. Aarn is a New Zealander who used to work for a lot of backpacking companies and finally, as a retirement project, started making his own packs, proudly emblazoned with the logo of the map of New Zealand. They are primarily sold on the South Island, where Aarn lives, and have acquired quite a following. His signature mark is a system inside the pack that’s engineered to put most of the pack’s weight on the hips through a dynamically moving hip belt and through the use of weight in the front of the body.

As a student of body movement practices, I was intrigued by the pack’s design the first time I saw it in New Zealand. It took me a bit of time to convince Brent that he shouldn’t be embarrassed to be seen with me wearing the green “boob bags”. I made the look a bit more palatable by buying the smallest front pockets Aarn makes. But now I’m thankful for these front pockets because they make my electrolyte drink and snacks available anytime I feel the slightest dip in my energy levels.

As the sun rises, we are high over the ridge, under the Catwalk, looking down on an impressively steep West Face. By this point, Matt is complementing me on my steady footwork and on not freaking out on the exposed slope as my ankles roll to hug the contours of the mountain with every step. Truth is, I finally had my own pair of mountaineering boots, not rentals, and a pair of fully automatic 12 point crampons, compared to the strap-on 11 point crampons that I had used in New Zealand. It made all the difference - my feet feel steady and supported. We follow the ridge, but unfortunately have to walk around the famed “Catwalk” as it was unprotected due to a rock slide earlier in the season.

Throughout the climb, I am hyper aware of the need to eat and hydrate regularly. I know from my earlier climbs and hikes with Brent that I am prone to keep my head down and just plough on until I inevitably bonk. Intentionally fueling my body before it keeled over became my driving mission on this climb. Even then, I could start feeling the altitude as we gain a few thousand feet from our base camp. My body starts feeling sluggish and my movements slow down. Still, I feel the mountain welcoming me with her benevolent presence. I feel comfortable on my short rope to Matt. I am falling in rhythm with his movements and pacing and I am getting immersed in my breath and the silence around.

And then it comes - the one mistake that I make, the only time that I allow myself to expend more energy than is called for. Matt lead climbs a short section of steep snow and sets up top rope belay for me to follow. Maybe it is the pattern of falling in synch with his movements the whole morning, maybe it’s the deceptive sense of full energy from eating and hydrating at regular intervals. Or maybe it was the excitement that I would finally use my ice ax and front-points to climb something more technical. Whatever it was, once I have the go ahead to start climbing, something compels me to really race up that hill.

Almost at the top, I feel it. The bonk. All of a sudden, I have to stop and rest. I feel the altitude like a heavy weight pressing down on my body. I don’t have the headache normally associated with the effects of altitude but at that point, I am at the highest altitude that my body had been exposed to since my hike on the Inca Train. Damn it! At our next stop, I feel completely drained and it’s decided that Tyler will continue ahead with the Caleb, while Spencer and Matt will wait a bit longer with me while I recover my energy. Starting at that point, our group climbs will stay divided.

A few breaks later, I am visited by the realization that the exposure of the ridge will continue all the way to the point where our route will merge with the popular Avalanche gulch route. This presents a problem as I badly need to “go”. And it’s not the type of bathroom visit that I can simply do with my trusty pee funnel. I relay my dilemma to Matt, who proceeds to scope out possible options. Finally, we come to a small rocky dip in the ridge that falls towards a steep gully on the West Face. There are a few rock outcroppings over the steep slope and a few rocks protruding from either side. Matt suggests that he hide behind the front rock and that Spencer, who’s walking behind me, wait behind the back rock.

I’m perched above a cliff, with my cramponed feet on a small rock outcropping each. It’s a dubious choice for a bathroom, but I really need to go, and besides, Matt has me short-roped from behind the privacy rock. But now I face another quandary. I have a rock climbing harness, which I need to undo in oder to drop my pants. As I get myself ready, I realize that my “protection” now lies wrapped around my ankles together with my undone harness. I just need to hurry and get done quickly. I use the large bio-compostable bag that I’ve brought for the purpose and try to get this over with as quickly as possible. There’s something really awkward about going to the bathroom while feeling the mountain wind blowing up my behind.

Finally, I pull my pants up and stand, poop bag in hand. Before I have a chance to pull up my climbing harness with the rope, Spencer, having seen me stand up, assumes that I’m good to go and comes over the back rock, dislodging a bowling-ball sized block of ice from the rocks. The block peels off and in slow motion heads towards my right leg. In a flash, I have a snapshot of myself in the Alpine Club’s Accident’s report as the “climber” who fell to her death with a poop bag in hand and a harness around her ankles. The ice block hits my leg but thankfully my balance holds and my foot stays securely planted. Upon hearing the noises, Matt’s head pops up curiously from the front rock: “What’s happening? Everyone ok?” I give him a big smile of relief - yes, alive! That’s when I make the decision to get an alpine harness that can come undone without removing the waist loop.

A few segments of relentless and monotonous slog up the ridge later, and we arrive at a snow flat where the route merges with the main Avalanche Gulch route. I’m starting to feel the heaviness of the altitude and the exertion of each step. As I get to the flat part, the weather has turned - the wind has picked up and the temperature has dropped dramatically. As I look up through the incipient mental fog, I see the bulk of another hill towering in front - it’s the part of the climb aptly named Misery Hill and it’s the part where a significant chunk of climbers quit. It’s the combination of hard work, the altitude and the realization that there’s still a significant slog up ahead just when you thought you were almost at the top. I know I’m facing my first mind game.

Matt piles the pressure by letting me know we’re getting close to our turnaround time. We have just under an hour to get to the top. I know it’s going to be close. I quickly chew a few energy gummies and put my nose to the ground. I avoid looking up for fear that there’s still a lot of Misery Hill left. I’m thirsty and the hose of my water bladder has completely frozen. But I don’t let my mind wander - I am completely focused on getting the next step done, and then the next step.

Finally the slope flattens out and we’re faced with yet another long stretch of walking. Matt points to a few spires prodding out in the distance like small versions of fairy tale mountains. These are lava flows frozen in time like giant needles. One of these clusters is the peak. What seems like an eternity later, we arrive at the bottom of the very last hill - 100 meters or so of “last push”. By this point, I’m realizing that instead of a splitting headache, my body’s reaction to the highest altitude I’ve experienced is manifesting in an upset stomach and a mounting need to throw up.

“I need a break. I think I’m going to barf” I tell Matt and Spencer as I plop myself down on the snow. A look of concern crosses Matt’s face and I realize that if I throw up right now, I may not have enough strength to make the last few feet to the top. I must look defeated and I realize that I gotta get myself together. I pull out a half eaten Vanilla Goo packet and bite on it. The goo is frozen solid, so it comes out the consistency of glue and it tastes awful. I see Matt and Spencer standing there in silence, looking increasingly worried. I need something to motivate myself to get up and drag myself up the mountain.

In a split second, the song comes. As soon as I hear the lyrics in my head, I break the silence, blasting an out-of-tune ugly sound that sounds more like a barbarian battle cry than a melody: “EEETS the FINAL COUNTDOWN! Ta-da-da-dAAA…. Ta-da-da-da-daAAAA! Ta-da-da-dAAAA… Ta-da-da-da-dAAAAA…. AAAAA!” I heave myself up and screaming the refrain to the song, I charge up the hill. Matt and Spencer break out in huge smiles. They know now I’m going to make it. The sun comes out as we near the top. I change my out-of-tune singing to “Here comes the sun, na-na-na!”. The small cluster of frozen lava spires that is the peak is small enough for only a couple of people to stand on. Matt and Spencer let me stand on the top.

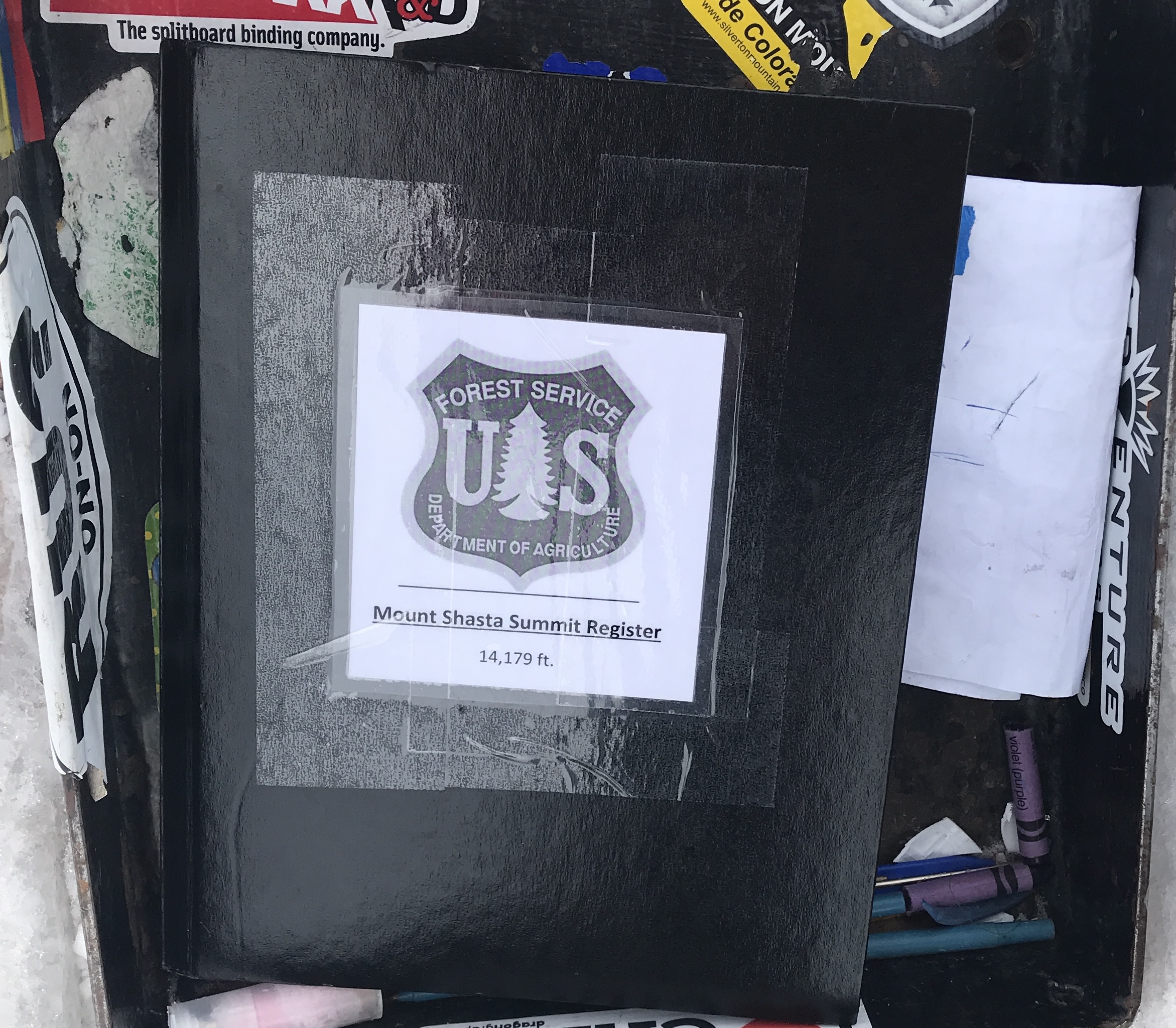

As I summit my first mountain in North America, I’m overcome by euphoria. I turn around and take in the view. I breathe in the air with full lungs. I raise my arms and let out a huge yell! YEEESSS!!! The tiredness and lethargy is gone. I start tearing up. At that moment, I strongly feel the presence of my dad there with me. I know he’s been climbing with me, supporting me and giving me strength. I also feel that Brent and mom are thinking of me the whole day. I get cell reception at the top, so I quickly text Brent and even reply to another random text from a friend who’s asking if I want to work for her company. Before we head down, I make a few entries in the summit register, kept in a heavy iron box near the peak. I enter Spencer’s name, my name and then my dad’s name. While I enter myself as having climbed “in person”, my dad gets the “in spirit” entry.

On the summit with Spencer!

My entry in the summit log

Coming off the summit euphoria, we start the descent and it quickly turns into a different type of a slog. Down from Misery Hill the wind and cold give way to a baking oven. We’re descending on the Avalanche Gulch route with the idea that we’ll cut over to the right and traverse to our campsite on the ridge before we hit Helen Lake, where most people camp overnight. My eager anticipation of a fun glissade gives way to disappointment as Matt declares that the snow is not soft enough to glissade. He wants the whole body to be sinking when the weight is spread out. There is just enough of a crust to prevent that.

I look with envy at the people who’ve climbed with their skis and are now skiing down in seconds what we are covering in hours with our cramponed feet. In my mind, I can’t wait to ski tour in New Zealand and experience the relief and joy of the quick descent. Ironically, in just an hour or two, the snow will be perfectly glissade-soft, but by that time we’ll be way over on the ridge slopes where we would be praying for crust and cursing the softness as we sink waist-deep into the snow on our crampons.

I’m eager to pick out the traverse line from Avalanche Gulch over to the ridge and a few times when I ask if “we’re on the traverse yet”, Matt explains patiently that the ridge looks a lot closer than it is because of an optical illusion. In fact, Matt is concerned that we may be starting the traverse too high, inadvertently walking taking a longer detour. Other guides have done it and Matt has been on trips where the lead guide has started traversing too soon, only to take an extra couple of hours to get back to camp.

It’s almost three o’clock by the time we start traversing the last slope on the way back to camp. By that point, it’s so sun baked that we’re breaking the crust with every step. Spencer, who’s the tallest and heaviest, leaves foot prints that are as tall as my hips as I try to follow them. I see the tents in the distance and the lonely figure of Larry, standing like a sentinel, looking at us. I know he must be worried because he never looks away. I’m grateful that someone’s watching us because it gives me strength as I flail and struggle to wade through the snow. It takes us close to an hour to cover the last few hundred feet.

We look absolutely ridiculous - like characters in some epic moving in slow motion, a version of the hobbits on the side of Mount Doom, using the last inch of their strength to complete their quest. That idea pops into my mind as I fall through the snow for the thousandth time and I can’t help it. I sit down and start laughing - a big, loud, relieved laughter that echoes on the slopes. I laugh so hard, my eyes are tearing up. I look at Matt, whose facial expression transforms from alarm and surprise to a huge smile as he registers that I’m laughing hysterically and not having a meltdown.

Larry welcomes us back to camp and immediately takes my pack. I’m thankful for his mother-hen attitude and I know it must have been difficult for him to spend the whole day in camp instead of climbing. At that point, it’s been 13 hours since we started the climb. I have just enough energy to take off my boots and crawl into my sleeping bag where I pass out for a few hours under the warming sun.

The following day we break down the camp and have an easy walkout. The only bathroom on the way is closed for maintenance and it’s only at the Bunny Flat trailhead that we can finally get rid of our stinky “waste bags” and take our boots off. A few curious people see me with my gear and inquire if it’s a long way to “hike to the top”. When a family with two young kids asks, I direct them to the Ranger Station for more details. My mind finds it hard to adjust to questions from civilization and I’m too tired to explain the difference between hiking and mountaineering.

Back in Shasta City, Larry takes off while the other climber and I take out Matt, Tyler and Spencer to their favorite burger place for a celebration lunch. Later, in the bunkhouse, Matt tells me he’s impressed by footwork and stamina and encourages me to develop more skills as a climber. He shows me a different approach to self-rescue and a knot that he likes better than the Alpine butterfly for glacier roped travel. The downside of that knot is that it consumes twice the rope of the alpine butterfly knot - we measure it on the table in the bunk house. Matt likes it better for jamming against crevasse lips precisely because it’s so much bigger - there’s a lot of “knot” to help catch on the ice and break a fall. He also shows me how to put in an ice screw without dropping it - the key being holding your hand slightly under when screwing, so you can catch it if it falls. I like Matt - he’s got the perfect combination of energy, determination and humor to be a good climbing teacher and partner. I certainly hope I will get a chance to climb with him again.

Driving back to the Bay Area the following day, I see the majestic silhouette of Mt Shasta disappearing in the rear view mirror and I feel grateful and blessed to have had my first North American summit with her.